Despite all of the darkness surrounding this year and the pandemic, there have been many graces—or, at least, opportunities for them.

For me, one of those graces has been the rediscovery of writing. Another has been the rediscovery of a good book.

In Iceland, there is the tradition of giving books as gifts on Christmas Eve. The cold, dark, and long evenings are then spent reading the gifted books. In fact, in Iceland, some 93% of the population reads at least one book in a year.

With that in mind, I offer here a few words about some of

the better books I’ve read this year. Perhaps one of them will find its way

into your hands or into the hands of one of your friends or family.

This list

starts out with three CS Lewis books. I normally wouldn’t be so Lewis-heavy or

even Christian-heavy to start, but these three books are part of his “Space

Trilogy” and should be described together. And I hope you aren’t turned off by

something described as a “Space Trilogy”—these aren’t really science-fiction

books, anyway. They are a “fairy tale for adults,” Lewis says and, more, he

doesn’t even like the term “space” as a descriptor of the world above. Rather,

he says, they should be called the heavens—because the word “space” makes it

seem like there is nothing up there when, in reality, there is a lot going on

up there.

In

brief, this short, gripping book revealed that I have—and you the audience has—an

incredible bias and prejudice. And you don’t even know it. And when you do

discover it, you will be floored—and will never be able to go back to it.

Books

that achieve such a thing in the mind of the reader is worth putting at the top

of such a list.

This is

the second book in the Trilogy and it is the best. And that’s saying something

given how tremendous an impact Out of the Silent Planet had on me.

Many who

read this book believe it is a re-telling of Adam and Eve. It is not. What it

is, however, is an attempt to reclaim in you a worldview you never knew. That’s

a heady thing: the concept of a “worldview”—that is, how you think the world to

be and what governs it and what contains it and so on.

While

not an explicitly religious book,

Perelandra can certainly affect one’s perception of religion (that is, if one connects

just a couple of dots). To quote someone who read this book as an agnostic: “I

thought the universe was too big for Christianity. After reading this book, I

discovered it quite reasonable to think that Christianity was big enough for

the universe.”

That Hideous Strength

This is

the third and final installment of the Cosmic Trilogy. It is also the hardest

to read because it is the most philosophical. It was also written after Lewis’

famous “The Screwtape Letters” and is, in my opinion, his perfection of that

book. The points made in The Letters are now refined and given flesh and a

moving plot as they are placed in a world with a modern-day feel. (Lewis, with

some eerie premonition, describes—a half-century before our time—our current

struggles with riots, media, and an academia separate from a transcendental

objectivity).

That is all to say that this book is not for the faint of heart or of mind. Nor is it for small children. Nor for the easily depressive. But it is tremendous, having been published in 1945. And, by the end of it, most readers are tired of playing nice and realize the need to have chests with bravery in them—or else live forever in this book’s world.

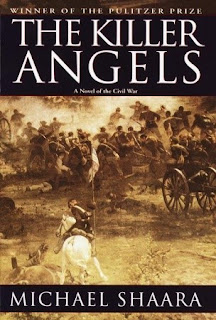

The Killer Angels, by Michael Shaara

In October,

I went on retreat in Virginia and, on my way home, I took a lengthy detour to

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Admittedly, I know little about the Civil War and the

Battle of Gettysburg—save that it was a major turning point in the war—and even

less did I know about Pickett’s Charge. So, when I visited the hallowed grounds

and then the Visitor’s Center, I asked the ranger there for a book

recommendation: “What is the best introduction ….?”

This is

the book she gave me. And it did not disappoint.

Far from

a description of the battle rife with military jargon, Shaara’s book gives an

inside look into the heart and mind and soul of the generals and colonels. He

does this having done a ton of homework

(reading the histories and the personal letters and journals of the men) for

which he won a Pulitzer in 1973. The result is a immensely readable and very truthful narrative that

not only gave me a deeper appreciation into the decisions—many tragic—behind the

battle, but also a greater appreciation for those who love the South and for why

many are correct in wanting to protect the statues of Robert E. Lee. It also

showed me the ignorance of those who simply argue “because racism”—but to

approach that with a level-headedness anyway; for, above all, Shaara gives—in fits

and starts—a greater reflection upon masculinity and what it means to be noble

and a gentleman (hint: reflection is crucial—as is its fruit: an appreciation

for those on the “other side”).

The

story is tragic as it is beautiful—and his description of tragedy at the end is

itself worth the read.

A Severe Mercy, by Sheldon Vanauken

I read

this book in my twenties and it made me fall in love with love and the beauty

of love. But this book is not simply an autobiography of two lovers. This is,

as Vanauken claims, a autobiography of Love Itself. And he’s right.

But this

is also one of the hardest books that you’ll read. It’s hard because his wife,

Davy, dies young and early in the book. (That’s not a spoiler—he tells you

straight away). It’s difficult because you see, as Sheldon retells of their falling

in love and then their struggles with impending death—it’s a difficult book

because you see what love can really, actually be. And that’s hard because,

having had that, he loses it. And so the question is asked: “Is it better to

have loved and lost than to have never loved at all?”

Full of

beautiful stories, descriptions of nature, poetry, pieces of music—the book

makes you sigh and laugh and cry and then laugh and then sigh again. And I’m a

guy.

But I

love how it addresses timely questions—“what is behind the failure of love in

couples today” and “how do I grieve and will it end and then what”?—by giving

profound (and not trite or preachy) answers. It was on that second question—about

grief—that this book hit home for me on this re-read. And it’s amazing that the

same book can bring about a totally different perspective on the second go-‘round.

And for

that reason, here it is on my list again. And why I made a special trip to visit their grave and to ask for their intercession.

Happy Are You Poor, by Thomas Dubay

Whereas “A

Severe Mercy” is a hard read, “Happy Are You Poor” is a dangerous read. A book is dangerous when, as you are reading it

(or, once you are done with it), you realize that you either have to jump over the

chasm in front of you or be swallowed by the chasm opening up behind and

beneath you. That is to say: this book makes clear that you have a decision to

make about life.

And that

decision deals with your addiction and dependence on stuff. (Merry Christmas).

Happy

Are You Poor was my spiritual reading and was written by a priest, Dubay, who

had made very-readable the lofty spirituality of St. John of the Cross and St.

Theresa Avila in his more-popular work “A Fire Within.” That one was more

popular because “spirituality” is easy when it can remain in the abstract. “Happy

Are You Poor,” however, makes it clear that spirituality must be concrete—or,

to quote Flannery O’Connor—to hell with it.

While at

times repetitive (because Dubay knows that some people pick up a book, read a

chapter, put it down for months, and then come back—or, even, that some will

only read a chapter that seems interesting in the Table of Contents), Dubay

offers a tour de force for arguing the importance of a simple life. And he was

writing this in 1984—long before minimalism was a thing.

Of

course, minimalism isn’t enough by itself—simplicity for simplicity’s sake—and so

he connects it with something deeper. And his critique of "comfortable giving" is

brutal.

By the

time I finished the last page, I had purged half of the stuff from my closet

and had totally re-worked my spending habits.

Something that can change life like that—yeah, onto the list it goes!

No comments:

Post a Comment